Turkish rugs displaying floral lattice patterns are fairly scarce, but interestingly enough they can be divided in two groups featuring two specific types of lattice, to be referred to as Saz Lattice rugs and Rumi Lattice rugs.

These patterns seem to have been quite fashionable in Ottoman silk textiles since the early 15th century.

The distinguishing feature of a large group of them is the use of shape design, deriving from numerous royal fabrics. For example one pattern - a main flower flanked by serrated lancet leaves - developed soon in an ogival grid receiving large flowers (plate 2). Small flowers - tulip, carnation, honeysuckle - usually grace the design.

|

| 1 - Silk velvet, mid 16th, possibly Bursa |

|

| 2 - Silk velvet, Turkey, mid 16th to mid 17th |

The saz vocabulary was quickly appropriated and used in court rugs. In particular, a number of Cairene-Ottoman rugs depicts scrolling floral compositions patterned by large saz leaves.

|

| 3 - Cairene-Ottoman rug, 1600 ca. |

Rare, nonetheless, are the extant rugs mimicing the ogival lattice as featured in silk textiles - the Saz Lattice rugs.

|

| 4 - Saz lattice rug, Turkey, 17th |

|

| 5 - Saz lattice derived rug (?),Turkey, (late 18th ?) |

Another group of Ottoman silk textiles depicts a different lattice distinguished by rumi leaves. The earliest examples are dated before the saz style arose in the 15th century, when Ottoman court art depicted the full blossoming of the Timurid International Style. Yet, fabrics in a plain rumi style (plate 6) are hardly found, since they are often seen with other motifs.

|

| 6 - Silk velvet with Italian influence, Turkey, 1480-1520 |

|

| 7 - Silk fabric with chintamani motif, Turkey, mid 16th |

|

| 8 - Silk lampas with saz flowers, Turkey, mid 16th |

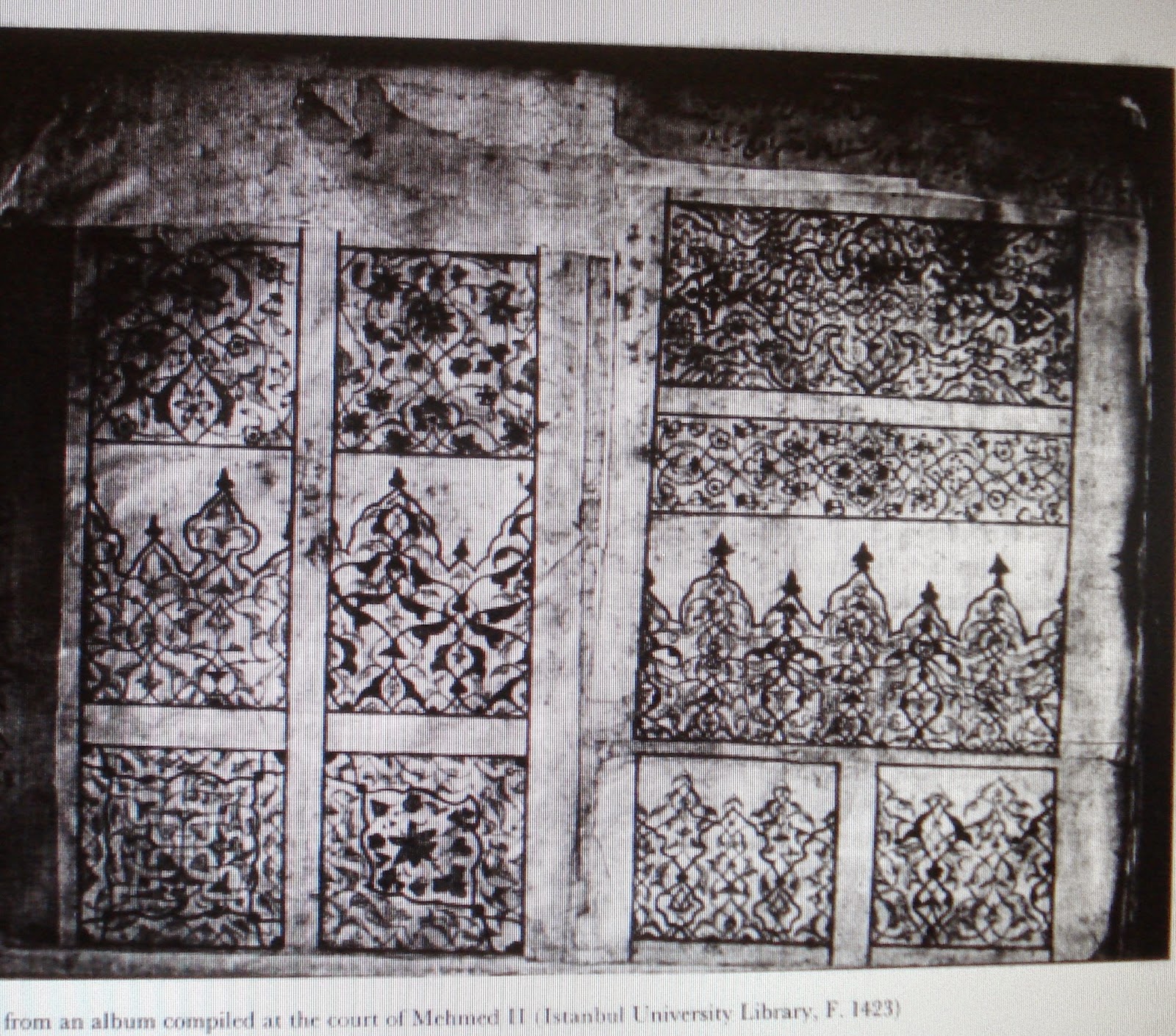

Otherwise, pure rumi patterns are well portrayed in early Ottoman tile revetments, in particular with two ceramic panels in Bursa and Edirne royal complexes. Masters of Tabriz, first hand learned in structures of the Timurid empire, were engaged to contribute to the royal buildings in the 1420s and 1430s.

Both works are conceived with the same system of interlaced arabesques creating a multilevel lattice, while an added compartment enriches the design with its eleborate knots. The whole layout is graced by the typical rumi flora, where the main element consists of the split leaf (plate 9).

|

| 9 - Murad II's complex, panel, Edirne 1426-36 |

|

| 10 - Mehmet I's tomb, Bursa, 1420s |

The Edirne panel seems to properly account for the design of a few rugs, which feature a rumi lattice - the Rumi Lattice rugs.

In the first rug the complex arabesque system turns into a plain lattice. Nevertheless, the weaver so faithfully depicted the varied rumi flora that the rug fragment can be considered a real embodiment of the International Style via the Turkish lexycon of an urban workshop.

A second fragment, despite the different style of the border, subtely conveys the same elegance of the original design by means of the rare white ground and a distilled rendition of the flora.

|

| 11 - Rumi lattice rug, Turkey, 16th |

|

| 12 - Rumi lattice rug, Turkey, 16th |

Most likely two more rugs belong to this group.

The rug (plate 13) declares its lineage by the dynamic shape of the lattice, where the rumi leaves and flora, although pretty summarized, are comparable with the above mentioned white ground rug.

Conversely, the the rug (plate 14) applies a fully geometric formula to the flowing arabesque style, but preserving the elements of the design: the palmette in the lattice intersections, the split leaves (by now just comb teeth), the flora.

Not an intrusive element, the multicoloured system of both examples belongs to the International Style vocabulary of chequered patterns, as depicted in numerous miniatures.

A last fragment (plate 16) is suggestive of a fading tradition.

|

| 13 - Rumi lattice rug, 17th-18th |

|

| 14 - Rumi lattice rug, 18th |

|

| 15 - Chequered-like field, Turkey (18th ?) |

|

| 16 - Compartment rug, Turkey, (19th, first half ?) |

Furthermore, the rumi lattice system was adopted by the famed Ottoman architect Sinan in Edirne - Selimiye mosque, 1568/74 - providing it with a saz livery, a most enduring one in Ottoman visual arts. Evidence of it is this later piece, where rumi leaves arrange an otherwise saz pattern. The Bergama rug (plate 18), in turn, testifies the long life of this design in knotted fabrics.

|

| 17 - Decorative panel, Selimiye mosque, Edirne, 1568-74 |

|

| 18 - Rumi lattice rug, 18th (?) |

Proof of the diffusion of this pattern in regions far from the court influence is a so called Sarkisla rug (plate 19).

Likely woven in Sivas-Dvrigi district by hands of Kurdish weavers, this piece is a classic example for the accuracy and elegance of its rumi stylised design: a split leaf enriched by the usual sprouting ornaments (calling them 'hooks' can be misleading in this case), small palmette in the four lattice intersections, large palmette in the top and end row.

These qualities seem lost in other rugs of this 'Sarkisla' group devolving into an unrealistic rendition (plate 20).

|

| 19 - Rumi lattice 'Sarkisla' rug, Eastern Anatolia (Sivas-Dvrigi), (18th ?) |

|

| 20 - Diamond lattice 'Sarkisla' rug, ( 18th-19th ?) |

Indeed a geometric vocabulary, though very basic, can be sensible to the original forms to be depicted, as in this 1800 ca. white ground rug from Cappadocia (plate 22). The intentional asymmetrical shape of the sawtooth leaf - likely a saz echo - looks like recalling a realistic shape and a dynamic flowing of the design.

|

| 21 - Selimiye mosque, edging decoration, 1568-74 |

|

| 22 - Lattice rug, Cappadocia, 1800 ca. |

---------------------------------------

We like to thank for the image credits - Alberto Levi Gallery, azerbaijanrugs, Moshe Tabibnia Gallery,The TIEM, tcoletribalrugs, rugtracker, Jozan magazine, 'Le décor du "Complex Vert" à Bursa, reflet de l'art timourid' by M. Bernus-Taylor.

Bibliographic references -

"From International Timurid to Ottoman: A Change of Taste in Sixteenth-Century Ceramic Tiles", by G. Neciplogu.Muqarnas 7 (1991): 136-70.

As kindly suggested by Alberto Boralevi - "Silk and Wool: Ottoman Textile Designs in Turkish Rugs" (re-published by T. Cole in http://tcoletribalrugs.com/article59Silk&Wool.html), by G. Paquin, "In Praise of God. Anatolian Rugs in Transylvanian Churches, 1500-1700", by A. Boralevi, Istanbul, Sabanci Museum, 19 April-19 August 2007.

Pinner R. and Franses M.: Caucasian Shield Carpets, in Hali, vol. 1, No. 1, 1978