|

| Anatolian carpet, 18th-19th (?), Saint Louis Museum |

|

| Anatolian carpet, 17th, TIEM Istanbul |

So far there is scarce evidence of specific silk fabric designs transferred to knotted carpets and yet they deviate from the original look.

Nevertheless, two carpets depict some silk patterns with some accuracy.

The sourcing models for both of them appear to belong to a specific group of silk velvets which are imbued with the International Style as developed from the 15th century in Europe and the Near East. There are indeed some fabrics still undecipherable as for provenance - Spain, Turkey or Italy.

The Turkish&Islamic Art Museum, Istanbul, preserves the older of the two pieces dated to the 17th century.

Gerard Paquin already pointed out its source in a definite velvet design. While the pattern repeats nearly the same after the small time span, its floral decoration is no doubt morphed into a proper Anatolian village vocabulary.

|

| 1 - Silk velvet, Italy or Turkey, 16th-17th, Gulbenkian Museum Lisbon |

|

| 2 |

Flowers and leaves (plate 3) are replaced by hooked geometric motifs imbued with an archaic zoomorphic lexicon (plate 4) that belongs to an as earlier as a different Anatolian tradition (plate 5).

The classical ragged palmette border, which in turn strictly adheres to the rug designs of the time, endorses, if ever needed, the transfer of the silk design to a rug type.

|

| 4 - Anatolian rug, geometric hooked motifs |

|

| 3 - Turkish silk velvet, 16th |

|

| 5 - Hooked motifs and animals, Eastern Anatolia, 17th by Balpinar, 15th by Yetkin-Aslanapa |

The City Art Museum of Saint Louis preserves the second piece dated to the late 18th - early 19th century (plate 8) - gift of Nellie Ballard White.

This rug was otherwise difficult to match with a specific velvet design. It seems, in fact, to borrow inspiration from two types mixed in a creative way - freedom plausibly due to the bigger span between the models and the rug itself. The design is based on a multilayered rumi arabesque pattern (plate 7) adjoined with elements of the floral meandering vine type (plate 8 ).

|

| 6 - Carpet, Turkey, 18th (?) |

|

| 7 - Rumi arabesque system, 15th/16th. |

|

| 8 - Spanish or Italian velvet, 16th |

|

| 9 - Petalled shape |

|

| 10 - Petalled shape |

|

| 11 - Rumi arabesque leaves |

|

| 12 - Rumi arabesque leaves |

|

| 13 - Rope-like vine |

.jpg) |

| 14 - Rope-like arabesque |

Unlike the previous rug, the Ballard one does not translate the velvet design in any traditional rug lexicon, displaying an almost straight version of it.

That is the reason why the rug does not appear fully consistent with a traditional Anatolian carpet code - it superficially looks 'imaginary'.

This particular look is specifically conveyed via two elements - the bizarre movement of the rope, as seen in plate 14, and the fragmentary nature of the repeat arabesque system.

Otherwise, the border pattern stands as warranty of the tradition, not a very common though.

|

| TIEM, Holbein type rug, border, 17th (18th) |

|

| TIEM, Lotto type rug, border, 18th |

.jpg) |

| Ballard rug, border, 18th-19th (?) |

---------------------------------------------

Updates, December 2018

A few more parallels between silks and Anatolian carpets.

It is well renown the visual arts to be influenced by one another in a long lasting process of mimesis. Likely due to parallel developments in royal workshops, it permeated also farther regions giving birth to an array of interpretations. In the TIEM, Istanbul, another fragment verifies the format of a single row of ogival arabesque clearly characterised by an inner and outer split leaf. The ogee transforms into an octagonal shape, the filling decoration simplified and masked by a fancy and almost bewildering layout. Plate 16 offers a comparison to design.

|

| 15-Floral arabesque fragmented carpet, Anatolia, TIEM |

|

| 16-Ottoman silk velvet, 16th/17th c. |

The relics of an Ushak carpet depict a repeat medallion interspersed with palmette and split leaf so as to create a sort of grid. Gifted in 1905 to the Royal Museums, Berlin, then devastated in 1945 by the war fire that injured the building, its medallion shape strikingly suggests a similarity with a Venetian velvet now in the Museo del Bargello, Florence.

|

| 17-Ushak medallion carpet, fragment, 16th ?, Museum of Islamic Art Berlin, photo courtesy John Taylor |

|

| 18-Venetian silk velvet, 15th, last quarter, Museo Nazionale del Bargello Firenze |

The parallel between the repeat medallion design in silks and carpets evokes the early artistic interplay between Venice and Istanbul (Venice and the Islamic World, 828-1797, Carboni 2007) rooted in a long and steady dialogue whereas at times it is hard to distinguish and clearly attribute a lineage (Ottoman kaftans with an Italian identity, Faroqhi, S., & Neumann 2004).

|

| 19-Complete Berlin carpet |

|

| 20-Turkish silk velvet, Ihalf 16th, The Metropolitan Museum |

|

| Medallion detail |

One astounding kaftan associated with Mehmet II (r. 1444-1481) and conserved in the Top Kapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, is a strong memento of this cultural exchange meant to show power and prestige. The Venetian fabric shows an elaborate and impressive design and technique, the same which Italian Renaissance artists associated also to sacred theme paintings. The use of royal kaftans tailored with Italian silks was not that unusual, typically in the second half of the 15th century. Italian silk manufacture was larger and earlier established than the Turkish. (Italian Silks for the Ottoman Sultans, L.W. Mackie 1999).

|

| 21-Silk velvet kaftan associated with Mehmet II, Venice mid 15th, Top Kapi Saray Museum |

Such velvets were quite influential on the style of life of the better-off dwellers from the second half of the 16th century well into the 17th, when less expensive and lighter garments were commissioned to the Venetian looms. The carpet in plate 2 testifies silk derived patterns spread in an urban less formal weaving context, as the completely transformed tiny decorations of the motif confirm: a villagy decorative 'dialect' replaced the courtly rhymes.

An Anatolian carpet formerly in the Alexander collection plausibly belongs to a similar fashion. Although much of a ghost, an ogival grid is still legible with inscribed large florons and minor stemming flowers alternating in vertical rows. With respect to plate 2, the weaver's effort to properly render the original model is clear yet not the result as in plate 6. Not strange again the parallel with an Italian silk velvet.

|

| 22-Italian silk velvet, 16th c., The Keir Collection/The V&A Museum |

|

| 23-Anatolian fragmented carpet, 17th c.?, formerly The Alexander Collection |

|

| Detail, Sotheby's image credits |

The next carpet of Anatolian descent displays a pattern loosely inspired to an Ottoman silk velvet design.

|

| 24-Floral carpet, Anatolia or 'Damscus', 17th c., Vakiflar Museum Istanbul, in Balpinar Hirsch pl.61 |

|

| 25-Ottoman silk velvet, 16th-17th c., Deutsches Textile Museum Krefeld |

Two more Anatolian exemplars, in the Berlin Museum of Islamic Art and in the Zaleski Collection respectively, give voice to a bold version of an ubiquitous theme in Islamic art sported in all visual mediums, namely the 'trefoil'. More often than not it decorates ornamental bands as if a floral fret, one classic version formulating a double reversed design via contrasting colours.

|

| 26-Ilkhanid ceramic frieze, 14th c., The David Collection |

A Seljuk period frieze in the astounding complex in Divrigi, Anatolia, great mosque and hospital, built 1228-29, unfold in the upper panel of a doorway a piece of a carved reciprocal palmette carpet.

Ottoman silk velvets do sport it as well. A diminutive version is included as minor guard stripes in some of the 'Transylvanian' rugs, likewise in the velvet below.

|

| 27-Ottoman silk velvet fragment, border, Bursa?, 16th., published Sovrani Tappeti pl. 4 p. 29 |

In the two carpets above mentioned the design has been used to decorate the field in a large scale ad infinitum, what seems to have been a practise in Anatolian carpets since an early date.

|

| 28-Trefoil carpet, Central Anatolia ?, 16th c. ?, Museums fur Islamische Kunst Berlin, pl. 17 p. 93, catalogue. |

|

| 29-Trefoil carpet, Central Anatolia, 16th c.?, Moshe Tabibnia |

As if in a backwards journey an Anatolian fragment held in the Metropolitan Museum (plate 30) leads to an earlier case, a fragment whose design may plausibly derive from a pattern widely used in Islamic art and in garments like a Mamluk Egypt folio painting seemingly verifies. Although the real robe pattern is not well decipherable, the painter tried to substantially convey it: a foliated intertwining motif with split leaf and bud. How may we otherwise call the carpet fragment's motif?

|

| 31- Mamluk Egypt circa 1325-50 Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper, The Aga Khan Museum |

Many other depictions from early painted books in the near East environs show a similar type of décor, enlightening what was a foliated arabesque in pure ornamentation (plate 32) and fabrics (plate 33). The fragment conserved in the Metropolitan might be one rarest survivor of a design quite on fashion in the period.

|

| 30- Anatolian carpet fragment, 14th/15th c., The Metropolitan Museum |

|

| 32- Maqamat al Hariri, Syria, dated 1237 |

|

| 33- Maqamat of al-Hariri Bibliothèque Nationale de France, dated 1222-23 |

In a later time we can find the same meme in an Iznik pottery sharing the painterly silk design to confirm, if ever needed, the conservative nature of Islamic art.

|

| Iznik dish, ca. 1600, Christie's ph, cs. |

At the end of the journey a carpet found in the Alaeddin Keykubad Mosque in Konya, Central Anatolia, capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rumi, declines a distinctive Chinese floral motif in the Seljuk period (1081-1307). The homologous design in a Far East silk brocaded robe (plate 35) dated to the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) enlarges the panorama eastwards along the Silk Roads whence kings and weavers had came just a handful of centuries before.

|

| 34-Seljuk floral fragmented rug, 13th/14th c., TIEM, photo courtesy rugtracker.com |

|

| 35-Chinese silk garment, late 13th, The Hermitage |

Probably an epigone of the genre, a similar pattern with the added bonus of interspersed ribbons still inspired weavers and commissioners some time later.

|

| 36- West Anatolian floral rug, 15th/16th c., Museum of Islamic Art Berlin, published Beselin 2011, photo credits rugtracker.com |

-----------------------------------------

Updates, March 2018

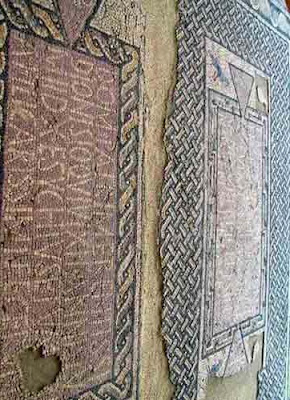

A carpet with the same derived design, a repeat lotus flower, harks back to the Moorish Iberian tradition. Held in the Textile Museum in Washington, it shows how far these eastern silk motifs could travel along the trade roads, but, rather, how intermingled were the different sources for Islamic carpets and, finally, Islamic art. Interestingly, the wide interlaced border seems to refer to the Roman art found in the Hispania province of the empire. A mosaic excavated in Sardinia, in the settlement of the Roman colony Turris Libisonis (today Porto Torres) , testifies to it.

|

| Spanish carpet, lotus scroll design, 15th, The Textile Museum Washington |

|

| Roman mosaic, Turris Libisonis, Sardinia (the picture has been turned verically to closer remind the carpet) |

One further acquisition to this entry is a cotton hand printed ceremonial cloth made in India for the Indonesian market 16th-17th. Its layout sports an unmistakable pattern seen in the beginning of this loose dissertation. As said, it was a typical 16th/17th motif in Ottoman and Italian silk velvets.

Although not a rug, it may epitomize the long run silk designs went through in the Golden Age of Ottoman empire.

But why Indonesia?

During the 16th century the Ottoman empire lived the enormous struggle for global dominance in the Indian and Pacific Ocean. Specifically, the Ottomans had good relations with the Muslim Indonesian Sultanate of Ache from the 1530s, and, in their struggle for the Indian Ocean trade control with the Portuguese, they intervened with an imposing fleet in 1565. The scope was to dismantle the power of the Portuguese empire of Malacca.

This alliance led to increased exchanges between Aceh and the Ottoman Empire in military, commercial, cultural and religious fields. Subsequent Acehnese rulers continued these exchanges with the Ottoman Empire, and Acehnese ships seem to have been allowed to fly the Ottoman flag. The Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent was acclaimed the supreme Caliph of Islam also in the remote lands of the Pacific Isles bestowing an unprecedented glory upon the empire (G. Casale, The Ottoman Age of Exploration 2010).

From the Mediterranean shores to Indonesia its enjoyed a century of fame and unique prestige. Not strange, then, local populations adopted some of the greatest global empire luxuries, and had made similar in the most prolific lands for worldwide textile trade, India.

Bibliographic references

Boralevi A., Western Anatolian Village rugs and Ottoman silk textiles", in “In Praise of God. Anatolian Rugs in Transylvanian Churches, 1500-1700” , Istanbul, Sabanci Museum, 19 April - 19 August 2007

Contadini A. and Norton C., The Renaissance and the Ottoman World, 2013.

Denny W., Ottoman Turkish Textiles, Textile Museum Journal III,3 1972.

Erdmann, K., Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets, 1970

Ertug A. and Kokabiyik A., Silks from the Sultans, 1996.

Franses, M., An Early Anatolian Animal Carpet and Related Examples, pdf in Academia.edu

Gursu N., The Art of Turkish Weaving, Istanbul 1988.

Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade 1500-1800, Metropolitan Museum of Art 2013.

Casale G., The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Oxford University Press 2010.

Peacock A. and Gallop A. T., From Anatolia to Aceh, 2015

Paquin G., Silk and Wool: Ottoman textile Designs in Turkish Rugs, 1996, in http://www.tcoletribalrugs.com/article59Silk&Wool.html

Silks, Tiles and Rugs, http://frafiorentino.blogspot.it/2015/01/silkstiles-and-rugs.html.

Spuhler F., Islamic Carpets and Textiles in the Keir Collection, Londo, 1978.

The Sultan's Garden: The Blossoming of Ottoman Art, The Textile Museum 2012.

Weaving Heritage of Anatolia, XIth ICOC.

Thompson J., Milestones in the History of Carpets, Milano 2006

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.