|

| 1 - Lotto rug, Sebastiano del Piombo, 1516 |

|

| 2 - Lotto rug, early 16th |

The prolific Ushak weaving district, Western Anatolia, most likely was the birthplace of a unique type of arabesque rug called after the name of an Italian painter who depicted them in at least two paintings in the mid-16th century - Lorenzo Lotto. Actually, such a patterned rug appears earlier in a portrait by Sebastiano del Piombo, 1516. Arabesque rugs are non really common in the Turkish output (see here 'Silks, Tiles and Rugs') - this one is really one of a kind and so well conceived as to get a long career both in its own home and abroad.

More than one diagram can be sketched on the pattern (one of them in plate 3), which unveils its underlying geometric modular system. Four units are pointed out - A and B are based on a circle or octagon, C and D on a cross or diamond - These are connected to each other by a shared element in a self-generating process typical of the 14th and 15th-century arabesque style. The design continuity together with the floral layout really sets this group of rugs apart.

A kinship with the Small Pattern Holbein rugs is often claimed, despite they share neither continuity of design (the two units are independent) nor a floral look (the units are composed by stars and knots). While the SP Holbein design has indeed an 'archaic' look, the Lotto one seems to belong to a rising Ottoman style in a period - the late 15th century - of great experimentation and crossbreeding. The Timurid style was undoubtedly one of the main influences

|

| 3 - Lotto rug, design units, 16th |

|

| 4- Small Pattern Holbein rug, 16th |

|

| 5 - Timurid Carpets, diagrams, Amy Briggs |

Similar patterns were plausibly used in other fabrics, though extant examples seem to be rare and their provenance hardly proved. One such item is a late Timurid period silk lampas depicting an allover design - two units of interlaced palmette&rosette within split leaves.

|

| 6 - Timurid silk lampas, Iran or Turkey, late 15th |

|

| 7 - Large Medallion Ushak, early 16th |

|

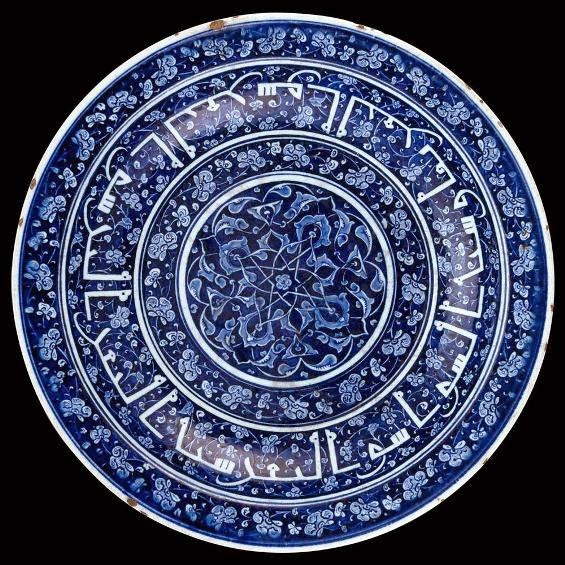

| 8 - Iznik bowl, 1480 |

Looking for design sources, tile revetments are often to be investigated.

Geometric modular systems with interlacing motifs were used to cover the masonries of early 15th century palatial buildings, as the Green Mosque in Bursa (1420s)

|

| 9 - Green Mosque, Bursa, 1420s |

Unfortunately many structures of the second half of the 15th century have only partly survived and their images are of a very bad quality. Often covered by later architecture and not yet unveiled by archeologists, the extant pieces testify, among others, the resilience of the floral arabesque patterned on geometric modular systems.

In the same period interlacing rumi arabesques with split leaves, palmettes and buds gave birth to a different type of rug design - no interlocked units, no selfgenerating design, just a repeat one .

|

| 10 - Turkish rug, simple modular system, 16th |

|

| 11 - Lotto interlocked units, 16th |

Two tile panels dated to the 1520s depict similar interlocked designs. The dating is plausibly slightly later than the Lotto pattern. Interestingly enough, plate14 suggests quite properly how the Lotto arabesque could have looked like in a curvilinear style.

|

| 12 - Top Kapi, Audience Room, 1527 |

.jpg) |

| 13 - Coban Mustafa Pasha Mosque, Gebze, late 1520s |

|

| 14 - Top Kapi, Circumcision Room, unit C type, 1529 |

|

| 15 - Lotto, unit C |

A later design in the Rustem Pasha Mosque (plate 16) shows two interlocking units based on palmette and split leaf in a cross arrangement (unit C), in particular it shares the same 'flat leaf' as the Lotto's one. Although the tile revetment of this building is one of the main epiphany of the new born Ottoman style as wanted and planned by the court, nonetheless elements of the previous influences can be detached.

|

| 16 - Rustem Pasha Mosque, Sinan, early 1560s |

|

| 17 - Lotto 'flat leaf' |

In the Lotto pattern the continuity of the design, the variety of the units, their ambivalence (cross, circle, octagon, diamond) and the neat two colours choice give to each of them an even dignity, the eye deceived in search for a dominant focus. Yet the many focuses create the specific fascination of the design, misleading the fixed nature of the allover pattern. The weavers must have been conscious of it. At times, in fact, they drifted from the plan enhancing it by colours and by focusing one or two units, always proving the long lasting vitality of the invention - stiffness lurking around the corner when the real nature of the design was not any more understood.

|

| 18 - Black Church, second half 16th, Brasov |

|

| 20 - Berlin Museum, 17th |

|

| 19 - A. Boralevi, 16th-17th |

|

| 21 - Small format Lotto, 17th |

The simple two colours choice for the field (yellow&red) - not quite popular among Turkish rugs - may have been sourced from the period gold&purple velvets with gold thread brocaded designs. In addition gilded tiles were a typical usage in the early Ottoman tile revetments enlivening the usual white&blue scheme.

|

| 22 - Ottoman silk velvet with gold threads, 16th |

|

| 23 - Green Mosque, Bursa, 1420s |

|

| 24 - Top Kapi, Audience Room, 1520s |

A few pieces display an even richer colour range, not necessarily related to a later phase - the purple velvet look definetely vanished in favour of a visual effect more common in a knotted carpet.

|

| 25 - A. Boralevi, Western Anatolia, 16th |

|

| 26 - Ex Halevim, Western Anatolia, 16th |

|

| 27 - Mac Mullan Collection, Western Anatolia, circa 1700 |

|

| 28 - Vakiflar, Eastern Anatolia, 18th (?) |

|

| 29 - Purple velvet look, Castello Sforzesco. |

Finally, the unique Lotto arabesque is probably indebted to the effervescent atmosphere of the court entourage, and to the experimentations of a rising art still looking at foreign models and training for its definitive assessment. No wonder if a proof of its court source will surface in the future.

Foreign artists were working together at the royal workshops or were invited to work independently for the court. Not strange if the urban laboratories felt as well free to assemble inputs from different media, as the case of our elusive pattern.

The Lotto arabesque - a tile design disguised as a gold&purple silk velvet by means of the knotted technique?

------------------------------------

Image credits

Alberto Boralevi; Christies Sales; Moshe Tabibnia Gallery; The Bardini Legacy; The David Collection; The Mc Mullan Collection; The Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin; The Museum of Art, Cincinnati, www.rugtracker.com: The Holbein-Lotto Family.

Bibliographic references

Balpinar B. & U. Hirsch, U., Carpets of the Vakiflar Museum, Istanbul, 1988

Batari, F., Five Hundreds in the Art of the Ottoman-Turkish Carpetmaking, Budapest, 1986

Boralevi, A. L'Ushak Castellani-Stroganoff, Firenze 1987

Briggs, A., Timurid Carpets, Ars Islamica, Vol. 7, No. 1, The Smithsonian Institution, 1940.

Concaro, E. and Levi A., Sovrani Tappeti exhibition catalogue, Milan, 1999

Denny,W. D., The Classical Tradition of Anatolian Carpets, London, 2002

Ellis,C. G., "Lotto" Carpets as a Fashion in Carpets, Hamburg, 1975

Erdmann, K., The History of the Early Turkish Carpet, London,1977

Ganzhorn, V., The Christian Oriental Carpet, Cologne, 1991

Ionescu, S., Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania, Istanbul, 2007

Mc Mullan Collection, Metropolitan Bulletin, 1970

Mills, J., "Lotto" Carpets in Western Paintings, Hali,3,4, 1981

Neciplogu, G., From International Timurid to Ottoman: A Change of Taste in Sixteenth-Century Ceramic Tile, Muqarnas 7 (1991)

Pinner, R., Multiple and Substrate Designs in Early Anatolian and East Mediterranean Carpets, Hali No. 42, 1988.

Schmutzler, E., Altorientalischer Teppiche in Siebenbürgen, Leipzig, 1933

Turkish Carpets from the 15th to the 18th Centuries, exhibition catalogue, Istanbul, 1996

Yetkin, S., Historical Turkish Carpets, Istanbul, 1981

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.