Chapter I - The Hecksher

|

| 1- The Hecksher palmette rug, 18th-19th |

The Hecksher 'palmette rug', believed by the common wisdom to be an 18th century weaving attributed to the vast Khorasan region adjacent to the preset day Turkmenistan (West Turkestan), remains a mistery.

While not assuming the mystery can be resolved, some findings on the subject can delineate influence from the Azerbaijan/Caucasian weaving style as well an unexpected distinctive Turkmen accent. Finally, the comparisons do help disclosing its strong unique character.

|

| 5 - The Wher Yomut main carpet, 18th-19th |

The border - The main trefoil border is usual in both period Azerbaijan and Khorasan pieces; the 'S' guard is again seen in Azerbaijan and Yomut carpets.

|

| 4 - The Keir palmette rug, Caucasus, 18th |

The field - The variety of the designs is apparent in the Caucasian rugs of the Khanates period ( 1735 - 1805), where a plethora of Persianate floral motifs were going to settle in the Transitional, Floral and Sunburst type.

Three main motifs along with some minor garnish the red field.

The first motif - The so called lotus open palmette neatly displays its origin, being referred to a specific Caucasian group decorated with this allover design (plate 8). Yet, the fan shaped calyx echoes some Turkmen floral types. The style displayed in the flower (plate 6) immediately stresses a tough rendition of the model.

|

| 6 -Hecksher lotus open palmette |

|

| 7 - Caucasian lotus open palmette, detail |

|

| 8 - Caucasian lotus open palmette rug, 18th |

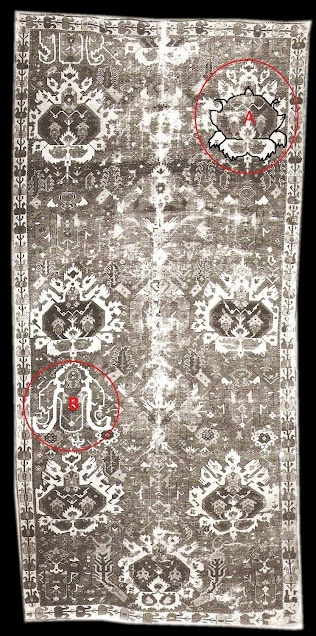

The second motif - Its high stylisation does not completely disguise a double palmette compound originated from the Safavid decorative pool (plate 9). Symmetrical palmettes are, in fact, often depicted in the Azerbaijan rugs (plate 10), in some of which a close inspection uncovers the source of the characteristic Hecksher motif (plate 11, fig. A). Curiously enough, the same rugs show the lotus open palmette (plate 11, fig. B), as well sourced from the Safavid floral vocabulary (plate 12). The double palmette will continue to be featured in some 19th century Turkmen and Kurdish rugs of Northeastern Persia.

|

| 9 - Karabak, Isfahan inspired palmette rug, late 18th |

.jpg) |

| 8 - Hecksher double palmette |

|

| 10 - The Keshishian sickle leaf rug, vase technique, Karabak, 17th-18th |

|

| 12 - Kirman, vase carpet, 17th, lotus open palmette |

|

| 11 - Palmette rug, Shirvan Khanate, late 18th |

|

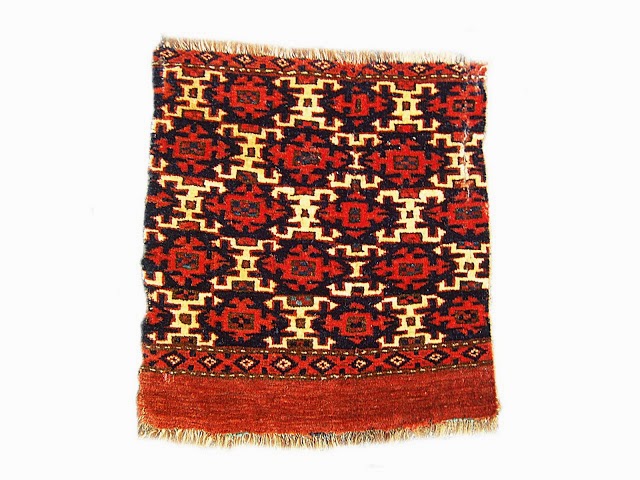

| 13 - Eagle Group torba, aksu gul, 19th |

The third motif - Despite seemingly similar to the aksu gul found in a type of the Eagle Group torba, it will be better discussed in the next chapter.

.jpg) |

| 12 - Hecksher |

Minor guls - Not well tipified, they loosely adhere to a generic Turkmen tradition. Two of them seem to take from the main and minor Salor guls, though losing the scale. The one and only stepped diamond inscribed with a cross design is seen in the inner decoration of theYomut carpet's guls discussed in the next chapter.

(Useful here to remind that Yomut, Salor and other Turkmen tribes were inhabiting the area from the Khorasan to the Amu Darya river in the 18th century).

.jpg) |

| Hecksher minor gul 1 |

.jpg) |

| Hecksher minor gul 2 |

|

| Salor main carpet, detail, 18th |

|

| Stepped diamond |

Chapter II - The Ballard

|

| 14 - The Ballard Yomut main carpet, 18th |

A carpet 'out of the box', the Hecksher is related to another famous atypical Yomut main carpet, the Ballard.

Unlike the previous, this rug bears the Yomut stigmas in the technical features and in two designs, the c-gul and the meandering palmette border. Cut and sewn longitudinally through the middle, it veils only part of the central axis motifs.

Despite the Yomut membership, again much of Persianate/Caucasian influence can be detected in the pattern. Very far from the calm and neat order typical of the early Turkmen main carpets, it displays a kind of dramatic prosody by means of big scale devices and sudden spots of light. Big designs closely assembled with no pause in between are again typical of some Khanates rugs.

The Ballard shares with the Hecksher two designs of Caucasian inspiration, both unfortunately cut and sewn - the double palmette and the lotus open palmette. The latter, though missing the central calyx, is apparent by the open petals almost sewn together (plate 15, fig A).

|

| 15 - The Ballard rug, detail |

With the exception of the c-gul, two more main devices are featured in the field.

The first - It is represented by two mirrored palmettes of Persianate inspiration inscribed in a serrated black halo adhering to the petals profile.

The second - It is an original complex gul whose source is uncertain, yet it seems logical to look for it in the Caucasian decorative pool from where other elements of these two rugs have been derived. In this case one type of octagonal compound can be considered for its characteristic decorative protrusions (plate 18). The early exemplars, as the Ballard and the Wher are, use the protrusions as decorative elements, while they usually become structural part of the device, as a simplified version in the Wher rug indicates (plate 20).

The first - It is represented by two mirrored palmettes of Persianate inspiration inscribed in a serrated black halo adhering to the petals profile.

.jpg) |

| 16 - The Ballard mirroring palmettes |

The second - It is an original complex gul whose source is uncertain, yet it seems logical to look for it in the Caucasian decorative pool from where other elements of these two rugs have been derived. In this case one type of octagonal compound can be considered for its characteristic decorative protrusions (plate 18). The early exemplars, as the Ballard and the Wher are, use the protrusions as decorative elements, while they usually become structural part of the device, as a simplified version in the Wher rug indicates (plate 20).

.jpg) |

| 19 - The Wher Yomut main carpet, complex gul |

|

| 20 - The Wher Yomut main carpet, simplified gul |

At this point we once more introduce the Hecksher third motif for it seems a blend of the aksu and the Wher simplified gul. Again a tough design.

Since research is a working progress, I add today (april, 4, 2015) an interesting Yomut torba, esteemed ca. 1800, whose guls rather curiously recall again the Hecksher motif, both for shape and design style. A developed form can be seen in the minor gul, the so called 'Erre' gul, of many yomut torba of the 19th century.

|

| Yomut torba, ca. 1800 |

|

| Yomut chuval, erre gul, 1860 ca. |

%2B-%2BCopia.jpg) |

| 21 - The Ballard minor gul |

Chapter III - The Wher

|

| 22 - The Wher Yomut main carpet, 18th-19th |

So far the Wher Yomut main carpet appears to be a valuable reference for our arguments, and a closer inspection can unveil some more information.

From a distance two guls of the so called Kepse type prove to have a progressive size like matching a palmette form much similar to the Ballard type. Furthermore, the red symmetrical protrusions seem to repeat the Ballard petals inside the black halo. In this perspective the latter likely anticipates the castellated profile of the Kepse gul. Generously, the Wher exemplar gives us as the hint for the sourcing model as the istance of its symmetrical adjustment (plate 25). Corroborating this hypothesis, one Yomut exemplar shows two conjoint kepse guls much recalling the arrangement of two conjoint palmettes in line with the Persianate tradition (plate 26).

.jpg) |

| 23 - Wher mirroring kepse gul |

.jpg) |

| 24 - Ballard mirroring palmettes |

.jpg) |

| 25 - Wher symmetrical kepse gul |

|

| Rugkazbah image |

|

| 26 - Yomut multigul rug |

|

| detail, conjoint kepse gul |

The floral origin of the Kepse and other two guls is consistent with the apparent floral decoration of the elem. Probably the main part of the carpet, the field, required a special aesthetic able to convey a proper symbology, while the elem accepted a more realistic rendition. The Wher curled leaf border, as well as the meandering palmette seen in the Ballard and other Yomut main carpets, would confirm a coherent floral inspiration for this type of weavings, not irrelevant also in other Turkmen types.

Although these pedestrian comparisons do not achieve anything conclusive on the Hecksher subject, they stress, if ever needed, the influential presence of Caucasian/Persianate models in some western Turkmen weavings by means of the cosmopolitan trade centres of the Amu Darya region. In particular, the Azerbaijan Khanates significantly traded with it via the Northern Persian region of Gorgan in the second half of the 18th century. The Gorgan and Atrak regions were inhabited since the 17th century also by the Turkic Goklan tribes, which were too responsible for weavings at times put close to the Salors, at times to the Yomuts. They seemingly wove a group of rugs with the allover double palmette design in the 19th century. That's why the Hecksher has been attributed also to the Goklans.

The Persian influence is reportedly surmised by the account of the Polish Jesuit Father Krusinski who lived in Persia from 1704 to 1729: He mentioned Astarabad, in today Gorgan, a site of a Shah Abbas laboratory. Carpets and other fabrics were to be made in its own manner with a strong Persian urban influence as in the other royal laboratories established in Karabak, Shirvan and Gilan. (See Pinner and Eiland, The Wiedersperger Collection, De Young Museum, 1999). Yet, each example got a unique accent..

Who were the weavers in these laboratories, were 'tribal' individuals employed to work on commission?

The Persian influence is reportedly surmised by the account of the Polish Jesuit Father Krusinski who lived in Persia from 1704 to 1729: He mentioned Astarabad, in today Gorgan, a site of a Shah Abbas laboratory. Carpets and other fabrics were to be made in its own manner with a strong Persian urban influence as in the other royal laboratories established in Karabak, Shirvan and Gilan. (See Pinner and Eiland, The Wiedersperger Collection, De Young Museum, 1999). Yet, each example got a unique accent..

Who were the weavers in these laboratories, were 'tribal' individuals employed to work on commission?

However, the same comparisons seem underlining different sources for the Ballard and the Hecksher exemplars. The dramatic lexicon and rhythm of the Ballard, does appear more related to the Caucasian Transitional rugs, while the Hecksher appears to take more from the Floral group with ordered field arrangements.

The tough rendition and variety of the sourcing models did not prevent the skillful weaver from creating a cohesive design imbued with a strong identity. Not an ordinary collection of random motifs, it has a logical disposition arranged by alternate vertical rows. They are provided with an ascending direction by means of their changing scale and colour; balanced colours and spots of white are apparent in the first half of the field and decrease in the upper section.

The strong styles featured in this rug, bold and graphic, continue to defy and pique the curiosity of all those who love these weavings.

The tough rendition and variety of the sourcing models did not prevent the skillful weaver from creating a cohesive design imbued with a strong identity. Not an ordinary collection of random motifs, it has a logical disposition arranged by alternate vertical rows. They are provided with an ascending direction by means of their changing scale and colour; balanced colours and spots of white are apparent in the first half of the field and decrease in the upper section.

The strong styles featured in this rug, bold and graphic, continue to defy and pique the curiosity of all those who love these weavings.

-------------------------------

Bibliographic references

An Enigmatic Main Carpet: the ex-Ballard MC, http://rugkazbah.com/boards/records.php?id=2358&refnum=2358

Carpets from Turkmenistan- Goklan, in http://weavingartmuseum.org/carpets/plate7.html.

Carpets from Turkmenistan - Yomut, in http://weavingartmuseum.org/carpets/plate2.html.

Eagle Group Primer, Rugtracker, http://www.rugtracker.com/2013/03/eagle-group-primer.html

Enciclopaedia Iranica, Central Asia: Economy from the Timurids until the 18th century, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/central-asia-xi.

Jourdan, U., Oriental Rugs: Volume 5 - Turkoman, 1996

Mackie, L., and Thompson,J., Turkmen. Tribal Carpets and Traditions, 1980.

Moshkova, V.G., Carpets of the Peoples of Central Asia (1970), in Oriental Rug Review, Vol. III, No. 1 through Vol. IV, No. 9.

Murray, E., Origin of the Turkoman Guls, Oriental Rug Review, 1982.

O'Bannon, G., et al.,Vanishing Jewels: Central Asian Tribal Weavings, 1990.

Pinner, R., and Eiland, M.,Between the Black Desert and the Red. Turkmen Carpets from The Wiedersperg Collection, 1999.

Poullada, P., Kizilbash from Khorasan?, Hali 156.

Reuben, D., Guls and Gols II, Exhibition of of Turkmen and related Carpets from the 17th to the 19th Century,2001.

Sienknecht, H., A Turkic Heritage, The Development of Ornament on Yomut C-Gl Carpets, Hali 47.

Thomson, J., Turkman, 1980.

Wright, R., Carpets in Azerbaijan, http://www.richardewright.com/0409_CarpetsInAzerbaijan.html;

Wrigh, R., Turkmen Carpets and Central Asian Art, http://www.richardewright.com/0612TurkmenCarpets_CentralAsianArt/index.htmlArt.

Yetkin, S., Early Caucasian Carpets in Turkey, Vol. I,II, 1978.

Yomut, Tribe without a Gul, Rugtracker, http://www.rugtracker.com/2014/09/yomutgol-without-tribe.html.

.jpg)

.jpg)