Who knows the reason why white ground carpets have since ever exerted a special fascination, as if white wool were not a usual commodity for weavers?

One would dare guess white wool did receive less processing than dyed wool, therefore it is more resistent to use. What happens with white colour in the Western imagination? Purity?Transcendence? Was it the same in the countries and traditions from which these rugs were sourced? Perhaps. Obviously, we, the Westerners and the 'others', share also similar symbolisms.

Let us just mention the Muslim canon of colours, each with its own meaning - according to the observation of Muslim scholars, white is on top of the scale as it is chosen by

Allah for the Prophet. It refers to purity and transcendence. The white lily plays a role in Christianism.

But white is not just one, white has its prism of shades. And, as they are connatural to the material (wool) as much they are redolent with complementing colours. This is for the reflecting nature of the soft glossy pile. Different fragrances imbue the all-encompassing colour. Various actions are induced in the beholder guided by the choice of the weaver.

Anatolian white ground carpets that survived from earlier periods are not that rare.

|

| Seljuk carpet, 14th, TIEM |

|

| Saph carpet, 15th (?)TIEM |

Here we consider a broad family illustrating diverse layouts - the so-called Bird and Scorpion, the Chintamani, and the Niche - reportedly attributed to the Ushak area and in some cases to Selendi, a village within it.

Curiously, the Bird and Scorpion recall the white ground tile revetments of the period (16th-17th century), and in fact, no bird flies nor scorpion creeps, but floral stylisations rhythmically punctuate the field, re-worked and stylised to adapt to the weaving and the local esthetical sensitivity.

|

Bird carpet, V&A

|

|

| Scorpion rug, Budapest 17th |

More properly, the Chintamani was a major pattern in rich textiles for costumes and furniture. It gained yet a role also in some carpets. Competing with the luxurious silk kaftan it graces the field of a group of 16th Cairene Ottoman carpets. Usually, it sports a combination of three discs and two wavy lines variously arranged, sometimes just the disc triad.

|

| Court kaftan, Ottoman, Topkapi Saray Muzesi |

|

| Chintamani, Ottoman Damascus tile 1550-60 V&A |

|

| Chintamani carpet, the Textile Museum |

|

| 'Karapinar' Small Medallion carpet (photo reconstruction) with triad motif. |

|

| Children's kaftan with triad motif, Ottoman, Topkapi Saray Muzesi |

Few more formats are punctuated by the mystical triad.

The Niche format manifests in two small classes. The first exhibits floral ornaments comparable to those woven in other urban or well-organised workshops. The second promotes a simpler geometrical layout and a coarse weave (one of the coarser in Ottoman Anatolian production, as Stefano Ionescu said).

To the first class belong some 6 items.

One is in the TIEM (it was impossible to get information from the Museum and elsewhere). It offers typical period designs although a crisp surprise arises from their arrangement. The spandrel ornament is a common Ottoman Anatolian motif (a gable leaf created by two split leaves closed to the apex added with tendrils). Usually woven in various colours, in this case, it is nearly monochromatic - almost an embroidery. The airy lace shelters at both sides the exquisite stepped niche profile from the multicoloured grand frame. And, how elegant la petit reprise of the stepped line surfacing amidst the descending tendrils in the niche flanks. The Prophet's sandals at the bottom field evoke the reason and scope of beauty and labour - pray and hymn to the Divine Presence - while the standard-like finial on top of the vault admits no diversion.

The spectacular border is shared by the Chintamani Rugs Club (woven in the same area). In the accompanying picture, a fragment of good age (late 16th) residing in the Philadelphia Museum epitomises it. A proper drawing of the reciprocal palmette motif associates chronologically the two.

|

| Niche carpet, TIEM |

|

| Chintamani carpet frag., 16th , Philadelphia Museum |

In the Bavarian National Museum, Munich, a sibling of the TIEM rests, with slight variants in the ornamenting designs and a somewhat collapsed niche shape. The Museum curator couldn't provide me with a colour picture and the pandemic impeded me from going there to study it (such a serious consequence for a rug lover!)

|

| Niche rug, Bavarian National Museum Munich |

Again in the TIEM rests a relative, not as fluently drawn. Stereotyped rather, as the schematically drawn border confirms. Question of age, presumably (Stefano Ionescu kindly informed me that the date inside the niche cusp reads 1726-27 by the Museum caption)

|

White Ground Niche rug, TIEM

One more beautiful exemplar dramatically changes the border, pretty charming and unusual yet. A precious addition to the canon.

| Sold at AAA 1914

|

|

Although there are no records of this pattern to be favoured in the European trade, Pieter Paul Rubens had one of these for a model in his powerful narration of Samson and Delilah's recount. A variation, though, for it depicts within the niche a floral tracery of a type similar to some woven in Transylvanian double niche carpets. The accurate border rendering (proper, detailed and schematic the least) gives trust to that of the field as well to an early dating, end of the 16th century. We should consider the early 17th century a likely time frame for the two sibling carpets - in the TIEM and Munich.

|

| P.P. Rubens, Samson and Delilah 1609-1610, The National Gallery London |

|

| detail |

The carpet delights us with a lush composition enhanced by a rainbow of colours (reportedly, a lush palette is a sign of age and rich workshop as well). The generous supply of yellow, apricot and pink conjures up sunny dawn as if the goddess Eos had woven it with her rosy fingers.

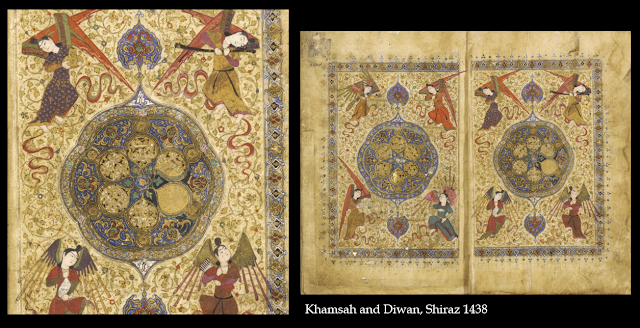

A rich woman, enamoured with the dawn-pink rug and jealous of the goddess weave, ordered the colour to be the theme of a pair for her luxurious rooms, and more luscious ornaments to go with it. That is why an arabesque - of Persian accent - scrolls through the frame of the carpet (once with the late Halevim) and steps moulded round draw the niche vault. More luxurious for an affluent setting (like miniatures confirm), the triad motif allusive of the leopard fur punctuates the bare field.

|

| The Ex-Halevim Niche carpet |

|

| Garden assembly, Safavid folio, Sultan Muhammad Tabriz 1520s |

|

| Incoronation of Selim I, 1512 Ottoman miniature. |

Dramatically divergent, a powerful, dramatic 'black & white' version exists to delight a 'dark lady' - the triad is lost in a simple poi pattern (which might mimic a cheetah skin), the airy tracery is solved into a simple creeping, a wrought-iron vegetal scroll inexorably locks the dizzy prayer within.

|

| The Ex-Bernheimer Niche carpet (18th century?) |

The speckled triad shows up in one more group of Anatolian rugs. Reportedly included in the same wide family from Ushak, where specialists distinguish those more finely woven from those less, those with more colours from those with less and, not least, those depicted with simplified geometrical patterns from those with a fluent floral style. Different workshops were at work, disparate financial resources, weaving abilities and commissions, and finally different markets. This group belongs to the less refined subgroup which received some favour in Transylvania in the 16th-17th century, as much as the less refined Bird rugs above mentioned. The village of Selendi has been pointed out by period documents as a sourcing place.

One of the most prized is the Boehringer carpet. Scholars seem to agree that this type belongs to what in an Ottoman 1640 document is mentioned as 'Praye rug - Selendi style with leopard design' (Inalcik, ICOC 1983). Indeed the term 'leopard' is never used to address the pattern with discs and waves. And, importantly, is an original, rare term that refers to carpet designs found in period Ottoman records.

Tracing back the source of the Chintamani pattern would simply confirm its antique origins - pre-Islamic - its various manipulations in diverse cultures and the impossibility of assigning to it a univocal description. Two main sources are mentioned - the leopard/cheetah pelt design (a powerful animal/symbol in formative periods of mankind) and the Sanskrit use of the term as a wishful-filling jewel, probably three pearls (Buddhism became probably a main vehicle of later diffusion for this motif).

Often, Ottoman art presents the three discs along with two waving lines - commonly attributed to the tiger pelt (one more significant animal in Eurasia). The populations from eastern and central Asia seem to have early prised the two assembled. Furthermore, leopard and tiger pelt seem to be a prerogative of costumes and equipment (horse saddle, scabbard, quiver) of nomad warriors who moved westwards from eastern Asia diffusing characteristics traditions and costumes.

|

| North China, Xianbei, 6th c tomb, Xianbei Museum |

|

| Uyghur fresco, 7th-9th, Bezeklik caves, the Hermitage Museum |

Nomadic traditions percolated in the varied uses of these fur hides transmitting the symbol of the hunter's value, the leader's power, hence the transfer of royal 'farnah' sort of from the animal to the person wearing it- god blessing, protection and favour.

Definitely highly prized, the leopard and tiger furs became a must-have in any affluent Turk context being often depicted in book folios in centuries till the 16th. Worn by important characters they testify high status. Interestingly, the folio below offers evidence of a leopard pelt carpet with cloud band border in a Safavid garden assembly (Rustam, the legendary Iranian heroe is typically characterised with a tiger or leopard cloak since earliest depictions). The Ottoman Turk use of it applies differently - the use of the chinatamani double design (waves and discs) is typical infact, and the single leopard spots as well. A way of distinction from the opponent Safavid power and cultural claims?

|

| Garden assembly, Safavid folio, Sultan Muhammad Tabriz 1520s |

Aside from the 'secular/royal' character of the animal pelt, interesting cultural associations are submitted by its religious traits.

|

| Meditation on a leopard skin, Timurid period folio, Central Asia |

Animal skins were early revered by Sufi masters (qalandars). They wore them as hide and ceremonial seats as well. Animal skins and pelts came to symbolise the perpetual presence of imams and saints to which by the tradition of hadits they belong. Dervishes particularly revered these fleeces to the point of prostrating before them as if in presence of their invisible owners. Indeed, because hadits talk of saints and important characters sitting each on their own animal skin when speaking and meditating, these skins became endowed with miraculous powers.

Traditionists trying to block these heterodox Islamic tendencies in the 14th century banned such 'blasphemous use, mentioning also the leopard skin. However, the practice was never erased. In Anatolia the legacy was in good part conveyed into the rising powerful Sufi brotherhood, the Bekhtashi order, which bloomed in Anatolia and the Balkans.

Whether this rare, small group of rugs with leopard pelt design still retain traces of the mystic narrative is impossible to ascertain. With certainty yet, they could bypass the Sultan edict, 1610, prohibiting trade rugs with religious signs (Qa'aba, mihrab, prophet's sandals, lamp) to unbelievers. That the edict was addressing only orthodox signs seems probable.

Their decorative system better fishes into traditional early motifs - the kotchanak on top of the vault, geometrical kufesque corner fillings, eight-pointed stars, whirling swastika and rosettes. They share a restricted palette and a simple, concise format with minute ornaments. The border lace-like decoration is typical of the group. It merits a dedicated issue.

|

| Leopard pelt niche rugs, rugtracker.com photocredits |

Some of these leopard rugs found their way to Transylvania where, presumably, their sobriety favourably engaged with the reformed Saxon Puritanism.

However, never forget the taste for exoticism. As a sign of status was quite diffused also in Northern and North-Eastern Europe.

|

| H. Mielich, Ladislau von Fraunberg, Count of Haag, 1557 |

Curiously, a carpet with the pelt speckles and a triangular niche reminder appears and decorates the inside walls of a city house in the Main Square in Tarnòw-Poland (photo credits to B. Biedronska-Slota), reportedly at the end of the 16h century.

Curiously yet conveniently, the parade closes with a rug format encompassing the main themes here touched upon - the white colour, the prayer rug and the animal pelt.

|

| Animal pelt carpet (prayer carpet), Anatolia, Vakiflar Museum |

Indeed, because the shayk, head of a dervish order, is termed pust-nishin, that is the one sitting on the animal skin, all along the 16th century (especially in Turkey and Eastern Europe, Kuhen 2018), and the dervishes used to pray over their takht-i-pust, that is a seat of animal skin as if a rug onto which perform the salat, it seems logic to recognize this rooted practices in carpets depicting animal skins.

|

| Dervish on an animal skin, Bijapur 17th |

Very few in Anatolia, these rugs share a basic field design - a rectangular shape with a kotchak motif at both ends and four legs. An earlier exemplar (here below) epitomises it. Kotchaks reportedly depicts ram's horns. Whether just sheep or any type of two horned domestic and/or wild four legged animals, they are redolent with the ancestral life-world and beliefs of Eurasian pastoralists and nomads deeply rooted also in Asia Minor.

Islam and its several branches quite soon adopted local traditions, although the traditionalists often tried hard to contrast the cult of wild animals. But sacred texts abound with saints sat on animal skins, the sheep's fleece one of them. Specifically, the Book of Poverty enumerates four different skins used by the mystics - that of the mufflon with spiralling horns one of them (two more are the skin of a liand of the black gazzelle with white legs and skin of a deer).

|

| Animal skin carpet, Anatolia |

Some period depictions could help identify the speckled surface of the fleece. Curls appear to characterise the long as well as the short type of wool. Possibly, the curl went simplified in the weaving technique into a tiny diamond.

|

| Indian painting of a dervish, 17th, exact copy of a Timurid folio 15th. |

Post scriptum

In as much so few extant rugs help to investigate the design, one could venture to submit that the tiny "c" punctuating densely the white ground of some Anatolian carpets - the Kiz Ghiordes group - could depict the curly wool flocks. Not differently the 'Karapinar' fragment already touched upon shows a speckled design.

We won't add to prove or enhance this idea the fact that sometimes the white reserve in these carpets looks like flayed skin. It is not actually. The characteristic shape is borrowed from the most famous Small Medallion Ushak format which is itself one of the many variants outsourced from the Ushak workshops during the 16th century. The four spandrels, and their typical drawing, are quartered large medallions where the principal indentation creates the well-known trefoil form - a cloud collar in fact. (see below the Yellow Ground Small Medallion Ushak as perfect proof).

|

| Karapinar Small Medallion carpet (photo reconstruction) |

|

| Yellow Small medallion Ushak |

|

| Kiz Ghiordes rugs (photocourtesy rugtracker.com) |

Typifying felines' pelt with a sort of pointillism rendition of the fur design is an early use indeed as this eastern Zhou dynasty exceptional jade shows, the features of the animal convey the image of a tiger as the Cleveland Museum curators suggest.

|

| Eastern Zhou dynasty, tiger carved jade, The Sam and Myrna Meyers Collection |

|

| Eastern Zhou dynasty, tiger carved jade, Galerie Zacke |

Bibliography

S. Kuhen, Wild Social Transcendence and the Antinomian Dervishes in A. Kallhoff, Morality of Warfare and Religion 2018

J. Rageth, A Selendi rug: an Addition to the Canon of White-GroundChintamani Prayer Rugs, Hali issue 98

S. Ionescu, Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania 2006

B. Biedronska-Slota, Turkish carpets in Poland 2011

Diyarbekirli and Pinner, Four Rugs in Aksaray, Hali 39

H. Inalcik in Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies, 1983

Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati, al-Faqr wa al-Thawra (The Book of Poverty and Revolution) 1965

Mushin al-Musawi, Arabic Poetry - Trajectories of Modernity and Tradition 2006