This paper was presented by the author during the 8th International Congress of the World Society for the Study, Preservation, and Promotion of Uzbekistan’s Cultural Heritage (WOSCU) "The Heritage of the Great Ancestors: The Foundation of the Third Renaissance" held in Tashkent and Samarkand, 23-26 August 2024.

Seven thematic sections were organized to discuss and debate required projects related to exhibitions in the halls of the Center for Islamic Civilization and the Imam Bukhari Museum. Francesca Fiorentino participated in the session "Architecture, Arts and Crafts"

The project was among the many approved.

The Paper aims to present the revolutionary impact of Timurid art on the new carpet iconography developed in the Safavid court ateliers.

It will show how the glorious Timurid Art of the Book was esteemed as an apex of Cultural Enlightenment. New achievements in the Safavid Golden Age will, in turn, influence the following centuries showing how Islamic Art could surpass differences and divisions in the name of the highest aesthetic values.

As such a long-lasting presence in Islamic Art and Civilization will appear.

Timurid Art received diverse impulses within the developing Islamic culture, a culture that acted as a porous ground able to host and adapt to diversity.

After the fall of the Timurid Empire, in 1506, a new political entity was ready to compete in the international scenario. In 1501 Ismail, heir of a Sufi Azeri order, proclaimed himself Shah of Iran. He shaped strong foundations for the Empire - vindicated religious ascendency from the seventh Imam and relied on ancient Iranian culture forged with and adapted to Shia Islamic values. He entertained tight relations with Turcoman clans and the Qizilbash, militant Shia warriors, and bearers of ancestral tribal legacy.

While the Safavids never claimed a Timurid lineage, they recognized in 16th-century historiography the continuity of the dynasty and presented Herat as the predecessor of the Safavid State.

Despite the war moved against the Shaybanids to reunite the Iranian core region of Khorasan and Herat in 1510, the Safavids had appeared as friendly guardians from a distance. Shah Ismail’s filial affection for Sultan Hoseyn is documented, while Herat served as a model for Qazvin, the second capital of Shah Thamasp. Let’s recall that Thamasp Mirza spent his childhood as Governor of Herat (1516-1521) and that the city became the seat of the Safavid heir apparent.

In that period was the Safavid turn to get intimacy with the culmination of Timurid culture in Herat.

Lamia Balafrej masterly describes the qualities of ripe Timurid art which we will associate with Safavid carpet features.

Aside from these aesthetic features some figurative themes prominently emerged in the painting - Moving Encampment, Royal Hunt, Park and Garden as a multifarious setting. Usual habits in Central Asian traditions since ancient times, in the 15th century, were finally included in the Islamic conventions with a rainbow of symbols.

All features here enumerated are to be found in Safavid court carpets roughly from the beginning of the dynasty to the early 17th century.

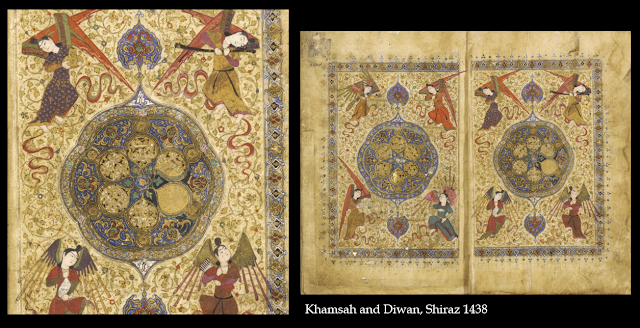

Nonetheless, Safavid ateliers could envision and

materialize in carpet patterns a unique novel blend. Figurative themes appear

within an array of decorative and fantastic drawings – spectacular solar disks,

hunters, noble characters, pavilions, thrones, fantastic animals, trees and

birds, angels and heavenly landscapes.

They manifested a magic variety of forms that claimed wonder and rarity. Great sophistication challenged the viewer’s understanding seemingly adhering to the canon of the ajab, the desirable experience of pleasurable wonder not being able to fully comprehend designs. Designs were again allusive and ambiguous figures overcoming the mere illustration of royal pageantry and power, as it was in late Timurid paintings.

Schuyler Camman in his studies on religious symbolism in Safavid carpets provides more information. He shows how visual and verbal puns used in their designs reveal hidden religious content. Safavid literati, in fact, delighted in subtle verbal plays solving riddles through verbal dexterity, a practice similar to the performances held in the Timurid majalis above mentioned.

Safavid designers dramatically innovated carpet motifs – they looked like painting designs accomplished with the best weaving technicalities.

In so doing they boldly departed from previous carpet patterns based on geometric designs and floral decoration.

Further on, as they encrypted

religious messages in a period of high spiritual aspiration, they closely equated

the sacred figurative Sufi painting of the late Herat, where an intertextual system

of signification combined literary discourse and mystic beliefs. It is not

strange, in fact, to find calligraphic scripts both religious and poetic that raise carpets to the highest culture domain.

Finally, the paper elaborates on how the new

achievements in the Safavid Golden Age prove Islamic Art to be able to always

bring new fruits.

It also suggests a greater Project – to illustrate the pivotal

role of the Timurid Renaissance in the development of Islamic Civilization. Significant

inferences will appear. One rarely underlined is the striking presence of green

spaces continuously interacting with Man as the best companion. The Islamic Garden convention

conveyed in so many precious paintings should represent an ‘early form of Ecology’ to a modern eye. Miniature Gardens are really a monument to the paradisical

place Earth can be, and to Nature as a gifted balm to body, mind and spirit.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A. Barfarah, Investigation of the Role of Shia in Political Revival of Iran in Safavid Era 2019

Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, Courtly Riddles, Enigmatic Embellishments in Early Persian Poetry, 2010

Bagh-e Nazar, The Impact of Timurid Gardens in Samarkand on Safavid Gardens in Isfahan (Chaharbagh), 2016

C. Melville, Visualising Tamerlane: History and its Image, 2019

C. Chia, Sufi orthopraxis: visual language and verbal imagery in medieval Afghanistan, 2012

L. Balafrej, The Making of the Artist in Late Timurid Painting, 2019

L. Golombek and M. Subtelny, Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century, 1992.

M. Gharipour, Transferring and Transforming the Boundaries of Pleasure: Multifunctionality of Gardens in Medieval Persia, 2011

M. Szuppe, L’évolution de l’image de Timour et des Timourides dans l’historiographie safavide du XVI e au XVIIIe siècle, 1997

M. Szuppe, L.’heritage centre-asiatique chez les Safavides, Table Ronde Tradition et innovation dans l’Orient ottoman et iranien, Mulhouse 1995

P. Berlekamp, Wonder, Image and Cosmos in Medieval Islam, 2011

S. Camman, The Interplay of Art, Literature, and Religion in Ṣafavid Symbolism 1978

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.