'...Oh morning Breeze, serve Khajeh Jajal al Din

and release jasmine and lily on the face of this earth'

(Hafez, 117)

|

| Lily, Safavid painting |

'The strong style featured in this rug, bold and graphic, continues to defy and pique the curiosity of all those who love these weavings'

|

| 1-The Hecksher Multigul Carpet, 18th (?) |

These words conclude an entry of the author on one most questioned carpet whose style and technique so far defy a safe attribution, the Hecksher Multigul Carpet. (https://limenonrugs.blogspot.it/2015/03/the-hecksher-co.htm)

Even its aesthetic value has been discussed, plausibly so, for it deceives any usual layout while mimicking more than one. Yet, its graphics has an undeniable visual impact.

Added here is an online version of Peter Poullada discussion regarding this weaving published in Hali 156, Poullada, P., Kizilbash from Khorasan? A Mystery Carpet from the Hecksher Collection

It appears, in fact, to be still a must read on the subject for it illustrates many points of view hardly enlarged so far. (https://www.dorisleslieblau.com/articles/qqizilbash-from-khorasan). However, the carpet still floats in the Limbus, no name, but his collector's.

It appears, in fact, to be still a must read on the subject for it illustrates many points of view hardly enlarged so far. (https://www.dorisleslieblau.com/articles/qqizilbash-from-khorasan). However, the carpet still floats in the Limbus, no name, but his collector's.

The 'polimorphic' gul (pl.4) and its source, although mysterious for Poullada, has been already explained like a doubled reversed palmette with calyx, derived from the typical Safavid 'in and out palmette' design (pl.2) and later stylised in Caucasian carpets (pl.3).

| |

|

|

| 4-detail of the double reversed palmette |

|

| 3-Palmette rug, Shirvan Khanate, late 18th, published in S. Yetkin (photocredit azerbaijanrugs.com) |

How far the palmette played a dramatic role in the Safavid carpet lexycon is already known .

|

| 5-Palmette detail, the Lafoes carpet, Safavid Iran, early 17th c. (photocredit rugtracker.com) |

In addition to these few marks, a further visual reference is here added: two 'Khorassan' carpets dated 17th century. They may be of some interest to enlarge the artistic panorama within which the Hecksher weavers could find inspiration.

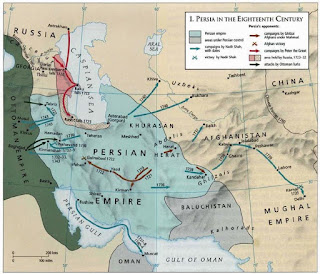

The Khorassan was a province of the Safavid reign bordering East the complex tribal basin of Central Asia and North-West the Safavid southern Caspian shores , Astarabad/Gorgan. This region was particularly infiltrated with Turkmen and was ruled for a period by an Uzbek amir till the arrival of Shah Ismail Safavid's troops. By the end of the 17th century, Astarabad was the main concentration-point for the Qajar tribe of Turkmen, comprising the Qoyunlū or sheep-herders and the Develū or camel-herders, and it served as the tribe’s base as it consolidated its power in the confused decades of the 18th century consequent on the fall of the Safavids. Here the first Qajar monarch was born.

Peter Poullada stressed the influence of the mixed Qizzilbash tribal groups in East Iran starting from the 16th century as forced displacements of clans and tribes from Anatolia and the Caucasus into Khorasan could bring. These eastern regions of the empire, although often dismissed as provincial, long retained much of their courtly status, the Timurid capital Herat still a myth as to courtly arts. But possibly their new status of military outpost against the Shaybanid Uzbek attacks and the Turkmen raids transplanted more of a tribal-Turk accent proper to the amirs controlling the borders.

While the Caucasian accent of the Hecksher has been safely sorted out by comparisons with 18th century exemplars, it is a call of duty to offer also a possible reference coming from Khorassan. Consequently, a specific design in the Hecksher will be more properly enlighted.

Two 'Khorassan' carpets are offered here for comparison.

|

| 6-Khorassan carpet frag, early 17th , Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin |

|

| 7-Khorassan carpet, 17thc., Austrian Museum for Applied Arts, Vienna |

|

| 8-Lily in the Berlin carpet |

|

It should be then investigate whether the Persian art created and imposed patterns, designs and motifs as the most revered cradle of art in the vast Islamic world.

Likely first cultivated in Minoan Crete, the lily spread East. In Persian is called susan from the ancient capital Susa built by Sargon to be the 'City of Lilies'. The flowers said to grace the royal gardens probably are the commonly called 'palmettes' seen in the later Achemenid ceramic reliefs. Allegedly, the Iranian nomads spread it West and East bringing the bulbus along as food. The lily is endemic in the southern Caspian shores (Encyclopedia of Cultivated Plants, by Christopher Cumo 2013).

|

| 10-Lily bush in the Heraklion Palace, Crete, Minoan civilisation |

|

| 11-Achemenid relief, from the Darius' Apadana in Susa, 6th c., Louvre |

The lily was a revered species ever since in the Persian culture. And, it was part of the Safavid floral decoration as variety was concerned, specifically in figurative settings.

|

| 12-Painted folio, M. Zaman, active 1649-1704, Safavid, Brooklyn Museum |

|

| 13-Cuerda seca tilework, 17th, Safavid, Aga Khan Museum, Toronto |

As to weavings, silk still got a good amount of 'realistic' depictions.

Otherwise, carpets apparently did engage a lesser 'realism' to the images. Designs often required a weighty degree of re-elaboration to be applied by myriads knot and a great variety and fantasy has always been added to the design.

|

| 14-Safavid silk fabric,17th, The Textile Museum |

Otherwise, carpets apparently did engage a lesser 'realism' to the images. Designs often required a weighty degree of re-elaboration to be applied by myriads knot and a great variety and fantasy has always been added to the design.

The 'Kirman vase carpets' (woven with the unique 'vase technique') include a significant class of floral designs wherein intertwining and undulating stems are punctuated by a stunning variety of flowers. Among the fanciest forms the lily. A quite stylised version is detectable also in Khorassan and Caucasian carpets .

This class of carpets specifically illustrates at its best a distinct quality of the period Persian carpet - the taste and almost cult for what we would call 'whimsy' forms. Painting did not at the same level, more anchored to figurative necessities, if not by extraordinary artists such as Behzad and few others. The narrative was often so imbued with fantastic and prodigious events to challenge a visual comprehensible rendition.

The 'Bizarre' is mostly limited to a few of the natural elements charged with a specific meaning like rocks, for Nature does actively partakes in the prodigious happenings of history, mythology and poetry basically melted together.

The flowers from Kirman, seem to have received a unique attention by a school of artists and designers whose history is still to be written and clarified. The sophisticated and fancy hybrids they created are not new in Islamic decoration yet unique and solely attributed to them: fruits as corolla, fantastic shapes, unrealistic supplement of decoration. More like marine concretions of concretions.

Impossible to forget the Master Painter at the Safavid court to be honoured with the appellation 'Master of the Rarities of Forms' and to be charged with a halo of sanctity, a pervading metaphorical sense pervading any of the Persian images.

In this perspective the strong stylisation of certain designs should not be considered that unfaithful to the original models within limits.

In Persian poetry the flower lily refers to eloquence and mimics a dagger in manifold metaphors of secular and spiritual love. Poetic sources since the time of the Firdausi's Shahnameh testify the lily to be widely cultivated to enrich the Persian gardens among lilacs, marigolds,jonquils, tulips, narcissus, anemones, carnations, cyclamens, poppies hyacinths, violets, and many others. Any of them and all together convey also a sanctioned image of the terrestrial garden mirror of the heavenly.

Three carpets from the Caucasus and East Anatolia sport a leafy grid encrusted with lily plausibly referring to a period (and local?) taste so as to be raised to primary design.

Hard not to question here whether it could otherwise be a tulip as one recalls the tulip mania exploded in The United Provinces (now Netherlands) in the early 17th century. A similar craze exploded in the Ottoman empire in the first quarter of the following century, called Lale Devri (Tulip Era). But, here the parallel with the 'Kirman vase carpets' design (pl. 9, 13), and its consistent morphing in the Khorassan and Caucasian exemplars, looks like more persuasive.

Would it be a lily, one could forget about the confused terminology referred to this motif: shield, open top palmette, tulip-like palmette and the likes.

|

| 15-'Kirman vase carpet', 17th c., V&A Museum |

This class of carpets specifically illustrates at its best a distinct quality of the period Persian carpet - the taste and almost cult for what we would call 'whimsy' forms. Painting did not at the same level, more anchored to figurative necessities, if not by extraordinary artists such as Behzad and few others. The narrative was often so imbued with fantastic and prodigious events to challenge a visual comprehensible rendition.

The 'Bizarre' is mostly limited to a few of the natural elements charged with a specific meaning like rocks, for Nature does actively partakes in the prodigious happenings of history, mythology and poetry basically melted together.

|

| 16-Kneeling figure, Behzad (1450-1535) |

The flowers from Kirman, seem to have received a unique attention by a school of artists and designers whose history is still to be written and clarified. The sophisticated and fancy hybrids they created are not new in Islamic decoration yet unique and solely attributed to them: fruits as corolla, fantastic shapes, unrealistic supplement of decoration. More like marine concretions of concretions.

Impossible to forget the Master Painter at the Safavid court to be honoured with the appellation 'Master of the Rarities of Forms' and to be charged with a halo of sanctity, a pervading metaphorical sense pervading any of the Persian images.

In this perspective the strong stylisation of certain designs should not be considered that unfaithful to the original models within limits.

|

| 17-'Kirman vase carpet, late 17th c., V&A Museum London |

'Even if Ḥāfeż had ten tongues like the lily, his lips would still be sealed, like a rosebud, with you'

(Ḥafez, d. 1390)

|

| 18-Nizami Quintet, Iskandar in The Enchanted Forest, Astarabad, 1560, Freer/Sackler Washington |

Three carpets from the Caucasus and East Anatolia sport a leafy grid encrusted with lily plausibly referring to a period (and local?) taste so as to be raised to primary design.

Hard not to question here whether it could otherwise be a tulip as one recalls the tulip mania exploded in The United Provinces (now Netherlands) in the early 17th century. A similar craze exploded in the Ottoman empire in the first quarter of the following century, called Lale Devri (Tulip Era). But, here the parallel with the 'Kirman vase carpets' design (pl. 9, 13), and its consistent morphing in the Khorassan and Caucasian exemplars, looks like more persuasive.

|

| 19-The Caucasus, trellis carpet, 18th, in Schurmann, Caucasian Rugs, pl. 94 |

|

| 20-The Caucasus or surrounding regions, trellis carpet, 17th/18th (photocredit azerbaijanrugs.com) |

|

| 21-East Anatolia, trellis carpet, late 18th (photocredit azerbaijanrugs.com) |

Would it be a lily, one could forget about the confused terminology referred to this motif: shield, open top palmette, tulip-like palmette and the likes.

Would it be a lily

The Hecksher Multigul carpet partakes also in a floral lexicon which in time and space lost the unfolding ryhme of rinceau and palmette as well as the trellis punctuation. Substantially, the influence of the floating Turkoman guls completed the result: a new breed, only one item of which solitary survives . So far from yet so imbued with courtly arts.

|

| 22-Reciting Poetry in the Garden, cuerda seca panel, Isfahan, 17th Ist quarter, The Metropolitan Museum |

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.